Russian President Vladimir Poutine surrounded by African heads of states during the 2019 Russia-Africa summit. © REUTERS / POOL

From October 22 to 24, the 16th BRICS meeting was held in the Russian city of Kazan, capital of Tatarstan, and the first since the “BRICS +” group expanded from five to nine members, now including Iran, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Ethiopia in the club of “non-Western powers”. Russia’s strategy of seeking to establish a foothold and integrate the countries of the “Global South” is evident above all in Africa, where it is re-establishing its military and diplomatic influence on the continent. Ten years is the time it has taken Putin to make this geostrategic shift, a priori a winning one, to the point of driving French and American forces out of part of the Sahel. While in 2014 the Kremlin annexed Crimea and intervened in eastern Ukraine, it was in 2017 that Moscow began to implement its African strategy, notably in Sudan and the Central African Republic. From 2020 onwards, the effort continues in the Sahel countries (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger) shaken by a series of coups d’état, while Serguei Lavrov multiplies his trips to Egypt, the Republic of Congo, Uganda and Ethiopia.

What interests does Africa hold for Russia?

With 17 million km2 and immense hydrocarbon resources, Russia is still a world power today. Nostalgic for its empire, it aspires to extend its influence. Its preferred terrain? Africa, a vast continent covering 30 million km2, with 54 states, countless resources and a young, dynamic population.

Russia’s presence in Africa has its origins in the Cold War. An IHEDN report speaks of a “two-headed” strategy, referring to the proximity of the USSR to South Africa, notably through its support for the ANC during the apartheid era, and the logic of the oppressed. In the 1960s, as sovereignist struggles set the decolonization process in motion against the former European powers, links were forged between Moscow and countries such as Modibo Keita’s Mali, Patrice Lubumbashi’s Congo, Sakou Touré’s Guinea, Kwane Nkrumah’s Ghana and Nelson Mandela’s anti-apartheid South Africa. Africa became a Cold War battleground, with the Western blocs and the Communists fighting each other by proxy. The USSR provided military aid to Communist regimes in Ethiopia, Angola and Mozambique. Russia’s strategy was also based on a broad university program for young students, with 25,000 students attending Moscow’s Patrice Lumumba University. However, following the collapse of the Soviet bloc in 1991, Moscow abandoned its projects in Africa.

Russia’s Post-Cold War "Soft Power"

Russia’s presence is measured by the influence it aspires to. During the Cold War, Russia tried to compete with the United States in terms of “soft power”, but since the 2000s, under Vladimir Putin, it has taken up this notion, building it less as a mirror than in opposition to the American model. The logic of influence and outward projection has been supplanted by a discourse of “confrontation with the West” and the image of a “besieged fortress”. The first symbolic step in this comeback was the President’s visit to South Africa and Morocco. Today, the discourse is based on friendships linked to the Soviet era, taking up the logic of the anti-imperialist, anti-Western struggle. The leaders of African countries see in Russia a new geopolitical offer that can serve their interests.

Without a complete obliteration of its concept, the notion of soft power has been ousted by “information warfare”. In Russian defense and security forces circles, commonly known as siloviki (“partisans of force”), one thesis is unanimously accepted: an “information war” would pit Russia, like the Soviet Union at the time, against “the West” (Zapad) as a homogenous whole. Information operations are not only seen as an issue to be considered in the operative art and as a weapon to conquer, dissuade, destabilize or persuade – they are part of a global rivalry between opposing “civilizational systems”, supposedly waging an undeclared war in the same “informational space”. This war incorporates a wide range of means, such as espionage, counter-espionage, disinformation, propaganda, cyber-attacks and the destruction of information systems.

Moscow relies on irregular means to wage this blurred war. Often extralegal, the strategies employed range from the deployment of mercenaries to support for coups d’état, military and industrial cooperation agreements, disinformation, electoral interference and arms-for-resources deals. Russia has become the number one arms trader on the continent, supplying 44% of African arms imports between 2017 and 2021, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Disinformation at the heart of russian strategy

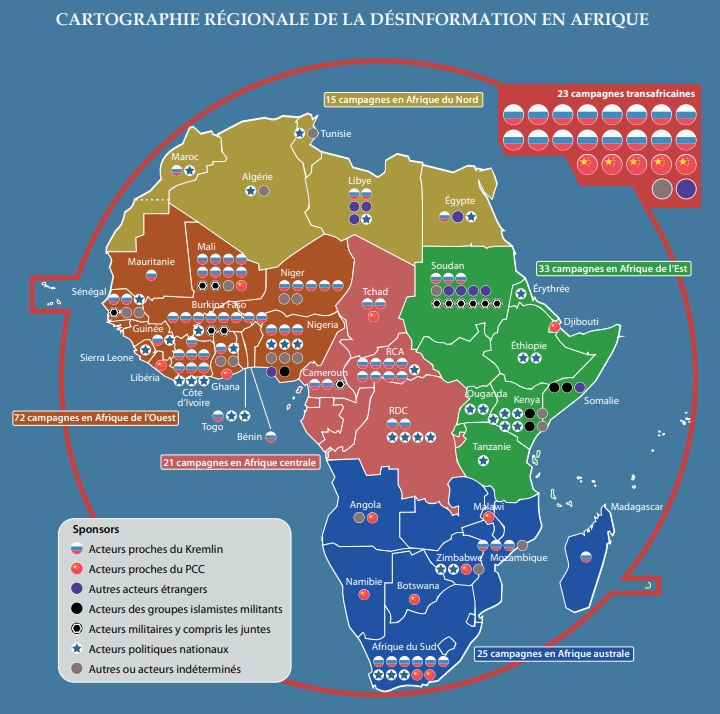

Russia is the main purveyor of disinformation campaigns in Africa, with at least 16 known operations on the continent. Of Stalinist heritage (dezionformatsyia), targeted disinformation tactics in Africa are adapted to Russia’s military strategy of “ambiguous warfare”. These campaigns have been carried out extensively across the continent. In May 2022, a video of corpses buried in Gossi, Mali, was relayed by pro-Russian influencers to accuse the French army of war. This disinformation was dismantled by the recording and broadcast on social networks showing Wagner militiamen installing the bodies. Russia systematically seeks to undermine democracy in Africa both to normalize authoritarianism and to create an entry point for its influence.

Disinformation campains almost quadrupled since 2022. © Centre d’études stratégiques de l’Afrique, 1er avril 2024.

Paramilitary presence: the infamous Wagner Group

Now renamed Afrika Corps, which is a dark callback to Rommel’s army, the infamous Wagner Group, once headed by Yevgeny Prigozhin, attempted to influence national outcomes and news narratives in some twenty African countries. Prigozhin, the face of Russia’s presence in Africa, reinforced the Kremlin’s indirect influence by supporting politically isolated and unpopular authoritarian leaders who were beholden to Russian interests. This support took various forms, such as the deployment of paramilitary forces and disinformation campaigns. In 2017, the first steps of the Wagner militias were taken in Libya, where they fought with the troops of Marshal Khalifa Haftar against the official government in Tripoli. They also fought in Sudan with former president Omar el-Bechir. Prigozhin’s holding company wins oil contracts in Libya and gold mines in Sudan. Russia gains allies against the West and a military base in Port Sudan, a strategic location on the Red Sea before the fall of Omar el-Bechir. Also in 2017, the rapprochement between Russia and the Central African Republic enabled Wagner to establish itself in Bangui, just as the French army had ended its peacekeeping operation in this country in chronic civil war. The Wagner company established itself at the heart of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra’s power base, exploiting diamonds, gold and forests, and financing several anti-French media outlets. In 2021, in Mali, the Russians make their biggest catch in the war of influence pitting them against France. After two military coups, the new government in Bamako chose the Wagner militia to fight against Sahelian jihadist groups, then sent French soldiers home the following year (end of Operation Barkhane). In the summer of 2023, it was Niger’s turn to be overthrown by soldiers demanding the departure of the French army, marking the fall of the West’s last and most fragile ally in the Sahel.

Prigozhin called this set of interlocking influence operations “the Orchestra”. The Kremlin-funded Wagner model of African wealth grabbing enabled Russian influence to expand rapidly in Africa, despite very little Russian investment on the continent. This tactic flouted human rights, as Wagner’s forces used rape, torture and extrajudicial executions as weapons of pressure. Since Prigozhin’s disappearance in a plane “accident” in August 2023, Russia has had to find a way to exert its influence without the group, and the government can no longer claim ignorance or impotence in the face of Wagner’s illegal and destabilizing actions.

Africa’s position in a renewed geopolitical landscape

In the face of current geopolitical challenges, Africa occupies a blurred position between Russia and the Western powers. The tipping point that projected African countries towards this Russian neo-colonialism was undoubtedly the Libyan civil war of 2011, which led not only to the fall of Gaddafi but also to chaos in the country and the spread of stocks of arms, munitions and fighters across the Sahel, creating armed groups against which Wagner is fighting to establish his hold. In addition to these brutal techniques, Russia, as a major grain-producing power, wields considerable influence over several African countries heavily dependent on its wheat exports, enabling it to brandish the threat of supply disruptions against a backdrop of food shortages exacerbated by the war in Ukraine. Russia is also using its weight in the hydrocarbons sector, notably as a member of OPEC+, to exert pressure on countries such as Algeria and Nigeria, the main African producers, not to increase their exports to Europe. At the same time, Moscow is conducting an active diplomatic offensive in Africa, multiplying Russia-Africa summits and seeking to circumvent Western economic sanctions. At the same time, Moscow is conducting an active diplomatic offensive in Africa, multiplying Russia-Africa summits and seeking to circumvent Western economic sanctions.