The second conference of ASPA’s “African Week” was held on Tuesday March 26, 2024 under the theme: “Gender equality, inclusion and entrepreneurship in Africa” and featured eminent and passionate speakers, all committed to promoting gender equality. A number of questions were addressed concerning women’s economic emancipation and entrepreneurship. In particular, how do g e n d e r inequalities impact populations on the one hand, and economic development on the other, in African countries? What initiatives can be taken quickly to remedy the situation? These were the questions addressed by our speakers, including Bathylle Missika, Head of the Gender, Philanthropy & Partnerships Division at the OECD, Vanessa Moungar, Head of Diversity and Inclusion at LVMH, and Emile Boyogueno, PhD, lecturer at Sciences Po and co-founder and Executive Director of the Institute for Economic and Social Research and Analysis (IRES-Africa).

What explains gender inequalities in Africa, and how do they impact on populations and economic development?

According to Vanessa Moungar, one of the most notable gender inequalities in the economic sphere is access to financial resources. The economic contribution of women in the private sector is undeniable. However, they remain marginalized when it comes to accessing the financial resources that could enable them to reach their full economic potential. This inequality remains a blight on the economy as a whole. For example, studies of southern African countries show that 90% of income generated b y women is reinvested in household expenses such as education, health and food, compared with only 35% of men’s income. Their ability to save, and therefore to grow their business, is therefore reduced.

According to Bathylle Missika, the main causes of these inequalities are :

- Formal laws, such as the lack of inheritance rights for women in some countries, which deprives them of the possibility of owning assets that could, for example, serve as collateral to obtain financing for their economic activities, thus limiting entrepreneurial opportunities.

- Informal tribal laws, such as early marriage, prevent women from training and developing skills to contribute to the job market.

- Societal perceptions, such as beliefs that women should not earn more than men, or that access to education is not essential for women, are also major obstacles.

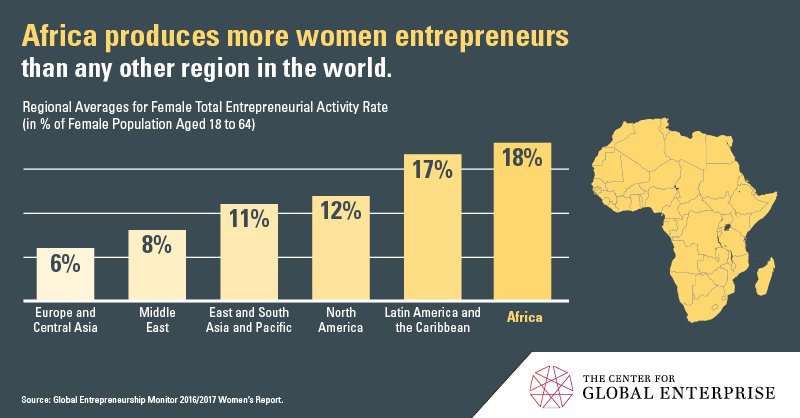

While the emergence of female entrepreneurship in Africa is often praised and presented as a means of economic emancipation, Emile Boyogueno was keen to qualify this reality. In most cases, entrepreneurship is not a vocation, but rather a default choice. Most of these women choose to launch their own business out of necessity, in the face of situations such as dropping out of school, unemployment or financial difficulties. Real women-owned businesses that create wealth are few and far between, and most activities generate little income. On the other hand, he pointed out that salaried women generally occupy lower positions than men for the same academic level. They also find it more difficult to advance professionally, often hampered by family responsibilities, maternity, etc.

How can we effectively eradicate these inequalities, and what are institutions like the AfDB doing to promote gender equity and inclusion in Africa?

Vanessa Moungar asserted that the AfDB’s Women’s Inclusion and Gender Equality Department has played a key role in establishing and institutionalizing the principles of gender equality through two axes. Firstly, “gender mainstreaming”, a policy which aims to ensure that in all projects supported by the AfDB, the inherent differences in the context of women and men are taken into account in order to reduce the gap between the two. Secondly, the implementation of targeted projects. The major project, known as AFAWA “Affirmative Finance Action for Women in Africa”, was launched with the aim of providing financial support to women entrepreneurs. Women entrepreneurs are often considered riskier borrowers by banks, as they generally lack solid collateral. The business model of institutions such as the AfDB limits the scope for direct intervention with small local entities (NGOs, SMEs, etc.). For example, it is necessary to justify the allocation of resources to the countries providing the funds; ensuring follow-up and traceability with small local entities can prove difficult to put in place. Nonetheless, the institution is stepping up its efforts with local partners, such as banks, to support women entrepreneurs.

Can we say that there is progress on this issue?

All three speakers agreed that there have been improvements in gender equality on the continent. Nevertheless, these advances are not yet commensurate with the efforts made, and there is still a long way to go. We need to educate, raise awareness and punish.